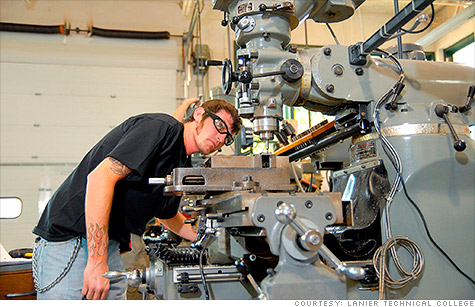

Many U.S. trade schools, such as the Lanier Technical College outside Atlanta, are seeing a jump in enrollment in manufacturing-related programs as need for skilled factory workers explodes.

NEW YORK (CNNMoney) -- Trade schools nationwide are bursting at the seams as demand for skilled factory workers pushes enrollment to record highs.

American manufacturers in certain sectors are enjoying a rebirth fueled by the return of overseas production back to the United States. As factories crank up, they have an urgent need for high-skilled workers such as machinists and tool-and-die makers knowledgeable in computers.

Trade school officials say manufacturing programs are experiencing an influx of students -- young people starting out, mid-career workers who are retraining after a layoff, and incumbent factory workers.

Workers are drawn not only by the opportunity but also the pay: Starting salaries of $50,000 to $60,000 are not out of range for high-skilled talent.

But the surge in enrollment is posing unique challenges for schools, many of which are running at or beyond full capacity for the first time in decades.

School administrators are clamoring to hire more instructors and secure funding to buy additional equipment and add classes.

These infrastructure limitations, and the fact that it can take a year or more to train high-skilled factory workers, mean that the current labor shortage could persist for several years.

Unlike 20 years ago, manufacturing today requires workers who are computer literate and skilled in computer-aided design and engineering, said Sandra Krebsbach, executive director of the American Technical Education Association.

Demand through the roof: The Dunwoody College of Technology, a private nonprofit school in Minneapolis, offers two-year programs in tool and die, computer-aided and robotics manufacturing.

Dunwoody will have 120 students across its manufacturing programs this year.

"That's the highest level of enrollees we've had in 15 years," said E.J. Daigle, the school's director of robotics and manufacturing.

For the first time in the school's 99-year history, Dunwoody will this fall introduce a six-month certificate program designed to fast-track training.

The program will allow the school to churn out an additional 40 graduates trained specifically in computer-aided manufacturing, said Daigle.

"Most of these fast-track students are older, in their 30s and 40s, who can't take two years off to go to school," he said, adding that these students have the option to return at any time and complete the two-year degree.

Demand for skilled workers has shot through the roof in his area, spurred largely by Minneapolis' robust medical devices industry led by Medtronic (MDT, Fortune 500), said Daigle.

"We graduated 20 students in June and we had 400 inquiries about them from manufacturers," he said.

It's a similar story in parts of Wyoming, said Ami Erickson, dean of agriculture and technical careers at Northern Wyoming community college in Sheridan and Gillette.

Demand for skilled workers in Wyoming is coming primarily from mining and natural gas companies, she said.

Both industries also have incumbent workers nearing retirement who will need to be replaced, Erickson said.

Starting salaries run as high as $80,000, and possibly more with overtime because of the worker shortage. Not surprisingly, the school's diesel and welding technology programs have large waiting lists, she said.

Erickson is on the hunt to add instructors in both schools but money is tight. "As a public school, we're funded by the state. Lately, we've had a pullback in funding," she said.

High-skilled workers are a hot commodity in Georgia as new manufacturers set up base, and existing ones expand operations, said Linda Barrow, vice president of academic affairs at Lanier Technical College, a two-year public school outside Atlanta.

"We expect enrollment in our programs will jump 8% to 15%, said Barrow. But accommodating more students is a challenge. "Our most hands-on classes have at most 20 students each, for adequate training and safety reasons," she said.

So the school's come up with a creative solution -- "virtual training."

Barrow said the school recently purchased a "virtual welding trainer" that allows students to learn and practice skills on a screen.

"If a student takes too long on a conventional machine, they can go practice on the virtual trainer," she said. "This way the whole class isn't held up and we can also train more students."

No comments:

Post a Comment